This video was created for a remote presentation at the International Communication Association (ICA) conference in 2021.

The presentation complemented an extended abstract submitted by me and my colleague Gwyneth Peaty. I recorded the presentation on my own, because when you’ve only got around seven minutes to play with it’s really difficult to coordinate two people! Also, clearly as you can all guess, this was left until pretty late in the time period set aside for creating and uploading presentations (although not right down to the last second)!

In the video, I’m talking about some early research Gwyneth and I have been doing in preparation for a larger project at Curtin University. What follows is a mostly true to the video transcript, edited for ease of reading, but with no additional information…

Introducing the research and the robots

Today I’m talking about communicating as/through/with a robot, so I’m going to be discussing human relations with telepresence robots. We’re using two very different telepresence robots to drive really what amounts to a number of different research projects.

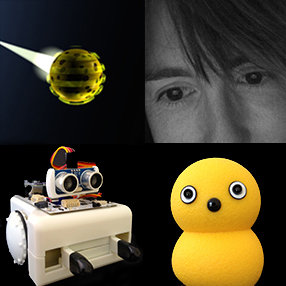

First there’s Sim, a mobile telepresence robot (MTR). This is a robot that’s described often as a machine that enables embodied video conferencing. The presentation video includes a picture of a Beam robot, which is another type of MTR that you might well have seen conferences. (This is the one I’ve actually seen in action.) I’ve included mention of that so there something familiar to more people, but the next slide contains an image of the Teleport robot that we’re using and have called Sim.

MTRs allow a person not just to be virtually present in a space or to interact and socially participate from a remote location through a screen; they also allow people physically to move in the local environment, around and with people.

In contrast, Haru is a very different type of telepresence robot: a tabletop telepresence robot. Some of these robots also have screens. Others do not have a screen and offer users a level of anonymity because of this. These robots also often provide other nonverbal communication affordances. You can see in the presentation video the OriHime robot, one of the screen-less robots mentioned in the extended abstract. Next the presentation shows Haru, from Honda Research Institute, a more complicated platform that has an expressive mouth, animated eyes and a neck that leans on a body that rotates. This means that Haru can really express quite a lot of different emotions, and its design was very much built around this sort of nonverbal communication at least in the initial stages.

I’ve already written a separate paper about Haru’s development (open access).

How to think about human relations with telepresence robots

Haru and Sim are definitely very different from each other, but they both allow people to teleoperate them and communicate through them in their different ways. At the moment, we’re looking at how to theorise telepresence relations (and the extended abstract does this in quite a lot more detail than the presentation). We’ve basically identified three different ways that you can think of telepresence and the relationship with a robot.

The first is the idea of being a cyborg…

This is something that Emily Dreyfus writes about in her experience with the robot she called Embot:

My head is her iPad, when she felt I felt this oriented in Boston. When a piece of her came off in the impact I felt broken.

You can see there’s a real cyborg relation here. Dreyfus feels an intimate connection with this robot as if it is just an extension of her own body.

The second is the idea of a human-robot assemblage…

If we think a little bit more generally about how telepresence works, it’s not necessarily the case that someone is going to be using a robot exclusively for their access to a workplace. So often, we have something that’s a bit of a less fixed relation, within which a human and robot remain separable and replaceable, because the participants, the human and the robot in fact, may change flexibly as required. You might have more than one person dialing into one robot, you might have more than one robot available and different people using them at different times. This less fixed relation can be thought of in terms of a human-robot assemblage. Here we’re extending some work that Tim Dant did in terms of driver-car relations with all sorts of cars.

This is work that I have already extended LINK when looking at autonomous vehicles (subscription required, but author’s accepted manuscript in Full Text on this site). Clearly, I’m quite interested in that idea of the assemblage. What it brings to light is a more flexible relation than, say, in the cyborg relation.

The third is the idea of humans and robots working together in a team…

When we consider some of the difficulties of using telepresence robots, we may want to retain an even greater sense of separation in the human-robot team. In particular, because it might be useful for telepresence robots to be semi-autonomous. They might be able to control the details of their movement around a space, or in the sense of robot like Haru, be able to offer pre-prepared, choreographed, emotive sequences of expression. We then have a sense where the human and the robot might feel more like they’re working together to produce a communicative result. They’re combining their different capabilities to enable effective telepresence, whether that involves moving around the space or being on a desktop and being very emotional in the presentation of that communication.

These are the three different means of theorising levels of telepresence or levels of closeness in a relation between a person and a specific robot that we’re considering at the moment.

Qualitative methods

The research we’re planning will use qualitative methods as its main strategy. Most of the research that we reviewed for the extended abstract used quantitative methods, in particular structured surveys, Likert, scales and associated statistical analyses. This all produces really interesting results, but I have to say that, as a humanities researcher, when I read the articles like that, I’m almost always more interested in why they’ve not used any formal qualitative methods. Some did use semi-structured interviews, while others used autoethnographic methods such as thick description. For me, these qualitative methods add weight to what the research was saying and add a sense of depth in understanding how people were experiencing telepresence. Our research is therefore going to use both interviews and detailed personal experience accounts to collect how our responses and the responses of our participants develop with both of these robots, Sim and Haru, even though they’re very different from each another.

Research questions

We’ve identified some potential research questions, but I think it’s worth pointing out these will be developed as we continue to work with the robots. We want to consider the perspective of remote users of the telepresence robot. So, we want to think about how people perceive themselves and the robot as they move through the space. We also want to consider how communication seems to work for them through a telepresence robot, how much are they thinking of themselves as the robot, communicating through the robot, or communicating with it. We’re also interested in how the experience of a communicative event when using a telepresence robot compares with people’s face to face communication experiences.

We also want to look at the perspective of people sharing space with the robot, to try to get a sense for how they see the telepresence robot itself and how they understand its presence, operating alongside the presence of the person that’s communicating through that robot. We want to understand how that interaction develops in that shared space. And we’re also wondering how the existing relationship between people communicating using these robots shapes their responses. Now, previous research that we talked about in the extended abstract looks at this mainly as an effect on the person who’s remote and using the telepresence robot, but we’re also interested, in looking in a bit more detail at how the people around the robot so in the same physical space as a robot also feel, depending on how well they know the person who’s using that robot.

This is really the extended abstract encapsulated in a very short presentation. If you want to ask questions you can ping me on Twitter (@elsand) or email me at my Curtin email address.