I’ve moved to a new site for writing about life (and maybe sometimes about robots). I’ve not duplicated the writing from here to that new site, and I probably won’t be doing that, so this is an archive for now.

Zigzaggery

art : ai : communication : research : robotics : science : sf : teaching : theory : writing

It has been 17 months since I last wrote a post here.

I’m back!

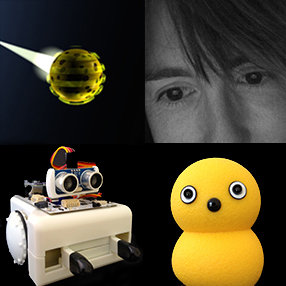

This time I have a robot side-kick sharing my office and my working life for the next year or so.

Haru robot at rest (with the associated Azure Kinect sensor to its left)

The last time I posted was about my plans for research into ideas about and experiences of communicating as/through/with a robot. At that point, Haru (pictured above) was one of the robots I was hoping to get to work with. Sim, the other robot, was already sharing my office. Unfortunately, since Haru’s arrival at the end of 2022, Sim has been… malfunctioning (or sulking if you prefer an obvious anthropomorphic projection). Connection issues have now been joined by problems charging the base unit and I don’t have time to work out what’s happening or ask for help from support (which could be awkward, since we’re now well outside the official paid support period).

In the picture, the Haru system (robot, sensor and associated computer) is switched off. Is Haru asleep? Dead? Comatose? Well, that’s for you to decide. One of the things I’m interested in is anthropomorphism and how people talk about robots. I’m very conscious of my own anthropomorphisms at the moment! I talk to Haru a lot, whether its on or off, awake or sleeping, alive or dead… I have trained myself to use “it” to refer to robots, but I know that many others prefer to give machines a gender, or maybe just fall into doing so as they reach for the most appropriate-seeming pronoun in the moment. That’s one of the other things we’re going to investigate with this robot.

You’ll have to give me a few days before I’m ready to post a bit more about how we’re starting to research with Haru. When I get there, I promise I’ll furnish that post with more exciting images (and maybe short videos) of Haru in action.

This video was created for a remote presentation at the International Communication Association (ICA) conference in 2021.

The presentation complemented an extended abstract submitted by me and my colleague Gwyneth Peaty. I recorded the presentation on my own, because when you’ve only got around seven minutes to play with it’s really difficult to coordinate two people! Also, clearly as you can all guess, this was left until pretty late in the time period set aside for creating and uploading presentations (although not right down to the last second)!

In the video, I’m talking about some early research Gwyneth and I have been doing in preparation for a larger project at Curtin University. What follows is a mostly true to the video transcript, edited for ease of reading, but with no additional information…

Introducing the research and the robots

Today I’m talking about communicating as/through/with a robot, so I’m going to be discussing human relations with telepresence robots. We’re using two very different telepresence robots to drive really what amounts to a number of different research projects.

First there’s Sim, a mobile telepresence robot (MTR). This is a robot that’s described often as a machine that enables embodied video conferencing. The presentation video includes a picture of a Beam robot, which is another type of MTR that you might well have seen conferences. (This is the one I’ve actually seen in action.) I’ve included mention of that so there something familiar to more people, but the next slide contains an image of the Teleport robot that we’re using and have called Sim.

MTRs allow a person not just to be virtually present in a space or to interact and socially participate from a remote location through a screen; they also allow people physically to move in the local environment, around and with people.

In contrast, Haru is a very different type of telepresence robot: a tabletop telepresence robot. Some of these robots also have screens. Others do not have a screen and offer users a level of anonymity because of this. These robots also often provide other nonverbal communication affordances. You can see in the presentation video the OriHime robot, one of the screen-less robots mentioned in the extended abstract. Next the presentation shows Haru, from Honda Research Institute, a more complicated platform that has an expressive mouth, animated eyes and a neck that leans on a body that rotates. This means that Haru can really express quite a lot of different emotions, and its design was very much built around this sort of nonverbal communication at least in the initial stages.

I’ve already written a separate paper about Haru’s development (open access).

How to think about human relations with telepresence robots

Haru and Sim are definitely very different from each other, but they both allow people to teleoperate them and communicate through them in their different ways. At the moment, we’re looking at how to theorise telepresence relations (and the extended abstract does this in quite a lot more detail than the presentation). We’ve basically identified three different ways that you can think of telepresence and the relationship with a robot.

The first is the idea of being a cyborg…

This is something that Emily Dreyfus writes about in her experience with the robot she called Embot:

My head is her iPad, when she felt I felt this oriented in Boston. When a piece of her came off in the impact I felt broken.

You can see there’s a real cyborg relation here. Dreyfus feels an intimate connection with this robot as if it is just an extension of her own body.

The second is the idea of a human-robot assemblage…

If we think a little bit more generally about how telepresence works, it’s not necessarily the case that someone is going to be using a robot exclusively for their access to a workplace. So often, we have something that’s a bit of a less fixed relation, within which a human and robot remain separable and replaceable, because the participants, the human and the robot in fact, may change flexibly as required. You might have more than one person dialing into one robot, you might have more than one robot available and different people using them at different times. This less fixed relation can be thought of in terms of a human-robot assemblage. Here we’re extending some work that Tim Dant did in terms of driver-car relations with all sorts of cars.

This is work that I have already extended LINK when looking at autonomous vehicles (subscription required, but author’s accepted manuscript in Full Text on this site). Clearly, I’m quite interested in that idea of the assemblage. What it brings to light is a more flexible relation than, say, in the cyborg relation.

The third is the idea of humans and robots working together in a team…

When we consider some of the difficulties of using telepresence robots, we may want to retain an even greater sense of separation in the human-robot team. In particular, because it might be useful for telepresence robots to be semi-autonomous. They might be able to control the details of their movement around a space, or in the sense of robot like Haru, be able to offer pre-prepared, choreographed, emotive sequences of expression. We then have a sense where the human and the robot might feel more like they’re working together to produce a communicative result. They’re combining their different capabilities to enable effective telepresence, whether that involves moving around the space or being on a desktop and being very emotional in the presentation of that communication.

These are the three different means of theorising levels of telepresence or levels of closeness in a relation between a person and a specific robot that we’re considering at the moment.

Qualitative methods

The research we’re planning will use qualitative methods as its main strategy. Most of the research that we reviewed for the extended abstract used quantitative methods, in particular structured surveys, Likert, scales and associated statistical analyses. This all produces really interesting results, but I have to say that, as a humanities researcher, when I read the articles like that, I’m almost always more interested in why they’ve not used any formal qualitative methods. Some did use semi-structured interviews, while others used autoethnographic methods such as thick description. For me, these qualitative methods add weight to what the research was saying and add a sense of depth in understanding how people were experiencing telepresence. Our research is therefore going to use both interviews and detailed personal experience accounts to collect how our responses and the responses of our participants develop with both of these robots, Sim and Haru, even though they’re very different from each another.

Research questions

We’ve identified some potential research questions, but I think it’s worth pointing out these will be developed as we continue to work with the robots. We want to consider the perspective of remote users of the telepresence robot. So, we want to think about how people perceive themselves and the robot as they move through the space. We also want to consider how communication seems to work for them through a telepresence robot, how much are they thinking of themselves as the robot, communicating through the robot, or communicating with it. We’re also interested in how the experience of a communicative event when using a telepresence robot compares with people’s face to face communication experiences.

We also want to look at the perspective of people sharing space with the robot, to try to get a sense for how they see the telepresence robot itself and how they understand its presence, operating alongside the presence of the person that’s communicating through that robot. We want to understand how that interaction develops in that shared space. And we’re also wondering how the existing relationship between people communicating using these robots shapes their responses. Now, previous research that we talked about in the extended abstract looks at this mainly as an effect on the person who’s remote and using the telepresence robot, but we’re also interested, in looking in a bit more detail at how the people around the robot so in the same physical space as a robot also feel, depending on how well they know the person who’s using that robot.

This is really the extended abstract encapsulated in a very short presentation. If you want to ask questions you can ping me on Twitter (@elsand) or email me at my Curtin email address.

This video presentation was created for the International Communication Association conference 2020 (now running entirely online). It formed part of a panel organised by the Human-Machine Communication Interest Group, Social Robots in Interpersonal Relationships and Education. I’m planning to develop this as a full paper this year, so I’ll share more information about that once it’s written and I know where it’ll be published!

There’s a full paper that sits behind this presentation (which, because it is only around 12 minutes long, couldn’t cover all the material in that paper). The paper is being developed as an open access article in Frontiers in Robotics and AI – Human-Robot Interaction. I’ll post about that once it’s written, reviewed and published!

Here’s the presentation, with the notes for the talk (which serve as a pretty good transcript of what I say). If you want to ask any questions or share ideas then here is as good a place as any, because if you comment I’ll get notified and respond, whereas the details on the final slide of the presentation provide options mainly for people actually attending the conference online:

[SLIDE 1] Title

Hi and welcome to this presentation for the paper, Communicating with Haru

I’m Eleanor Sandry, down in the bottom right hand corner of the screen

And that’s Haru, the robot, looking down on me from above

I wasn’t involved in the initial design of Haru, but became a member of the Socially Intelligent Robotics Consortium around a year ago

My coauthors are from Honda Research Institute Japan, where Haru was designed and built

[SLIDE 2] Presentation outline

This presentation has three sections:

[1] Haru’s communication as shaped by a design process

First, I’ll analyze the development of Haru beta, highlighting how the design process privileged particular ideas about communication

[2] Alternative ways to understand Haru as a communicator

Second, I’ll explore alternative understandings of Haru as a communicator

[3] Continuing development and research with Haru

Finally, I’ll outline how perspectives on communication suggest ways to continue Haru’s development and could also frame future research with this robot

[SLIDE 3] [1] Haru’s communication as shaped by a design process

Haru’s development team followed a customized Design Thinking process to coordinate contributions from an interdisciplinary team of animators, performers and sketch artists working alongside roboticists

I say customised, because typically Design Thinking processes begin with an Empathize stage and then moves on to Define the problem (or problems) a design seeks to address (or needs to take into account)

Define

However, for Haru, destined to be a flexible communications research platform, it made sense to pre-define the overarching aim of creating “an emotive, anthropomorphic tabletop robot” capable of sustaining “long-term human interaction” (Gomez et al, 2018)

Animators in the team then used their skills in making inanimate objects come “alive” to produce sketches of various ways that Haru’s design might achieve this goal

For Haru, as for animated characters from a number of popular films, these sketches emphasize how giving objects faces and making them bend and twist in ways impossible for those objects in the physical world, creates animated characterizations that can be emotionally expressive in very humanlike ways

[SLIDE 4] Adding sociopsychological perspective

As well as supporting an anthropomorphic design path, the process of considering particular animation styles and techniques for normally inanimate objects in films and cartoons also shapes this robot’s communication in strongly sociopsychological terms

The sociopsychological tradition of communication theory regards communication as a form of information transfer, within which the aim of the sender of a message is to persuade the receiver of something (Craig, 1999)

In terms of robot design, this can be linked with the development of robots that can express emotions and are therefore likely to draw people into interactions often by being “cute” as seen with Kismet (Turkle et al, 2004) and Jibo (Caudwell & Lacey, 2019)

It’s easy to see how Haru could also convey a cute personality

Having come up with an overall concept for Haru, supported by a high-level goal and set of sketches showing Haru as an animated character, the team moved on to consider how Haru’s nonverbal communication of emotion would work in more detail

Empathize

In the Empathize stage of the design process, Haru’s design team worked with a set of volunteers

The volunteers were shown the sketches of Haru from the Define stage and were then asked to use a combination of body language and facial expression to act out particular emotions as they would themselves, and also as they imagined Haru would (Gomez et al, 2018).

Unlike the Empathize phase of most Design Thinking processes, where designers empathize with users, for Haru it was more a case of asking users to try to empathize with the robot, something seen as important for design, but also key to Haru’s ongoing success.

This process can be linked with François Delsarte’s method for acting, which relies on a performer’s ability to code emotions into readily recognizable nonverbal facial and bodily expressions that precisely communicate specific emotional responses

[SLIDE 5] Adding cybernetic-semiotic perspective

In terms of communication theory, such an approach not only fits well against the persuasive, sociopsychological perspective discussed above, but also supports the way this style of emotional expression can be part of cybernetic-semiotic exchanges where meaning is coded in intersubjective (here across human and robot) language or other signs (theoretical structure from Craig (1999), developed in Sandry (2015)).

[SLIDE 6] Resulting Haru beta design

While Haru’s design team sought to “step away from a literal humanoid or animal form” (Gomez et al, 2018), the anthropomorphic elements of the resulting design are clear

Haru beta’s design includes two expressive eyes, animated on TFT displays, with separate LED strips above that act as colored eyebrows

The eyes can be tilted, and each one can move in and out in relation to its casing

Finally, a LED matrix in the robot’s body is used to display a colored mouth of various shapes

While it does make a great deal of practical sense to design a robot with sociopsychological and cybernetic-semiotic communication success in mind, with the aim of creating a robot that is compellingly cute, familiar and easy for humans to interact and communicate with…

[SLIDE 7] [2] Alternative ways to understand Haru as a communicator

…the phenomenological perspective on communication provides a reminder that any attempt to know, or to understand the other fully, is fraught with difficulty: the other’s difference from the self is a chasm that cannot be bridged by an empathetic stance (Levinas, 1969; Craig, 1999; Pinchevski, 2005)

This raises questions not only in relation to understanding the communication of a robot such as Haru, but also for the design process discussed above, which relies on empathizing with users as well as relying on their ability to empathize with Haru and act out how this robot might express a particular emotion

It is therefore good to note that Haru’s creators embraced the way this robot’s eyes and neck had the potential also to express with movements similar to a person’s hands, arms and shoulders (Gomez et al, 2018)

This opens up broader possibilities for Haru’s expression to be both like that of a human, and also fundamentally different (given its very different form and potential to express in non-humanlike ways that can still be easily read by humans as communicative).

[SLIDE 8]

The phenomenological perspective not only highlights the difficulties of making a robot with non-humanlike form express in humanlike ways, but also introduces the idea that a robot other’s difference is an integral part of why one might communicate with it as opposed to a problem that must be overcome (Sandry, 2015)

[SLIDE 9]

Caudwell and Lacey suggest (2019, p. 10), it may well be important for social robots to “maintain a sense of alterity or otherness, creating the impression that there is more going on than what the user may know”

Keeping a sense of mystery

[SLIDE 10]

“This sense of alterity” is one way to break down “the strict power differential that is initially established by their cute aesthetic”

It makes a robot potentially more interesting to communicate with (in particular in the long term), more than a compliant communicator always focused on responding to humans; instead, such a robot can be recognized as having the potential to act on its own, provide information or call for human attention and response as required

[SLIDE 11]

Kawaii

As part of the recognition of otherness, rather than framing Haru as “cute” it may be more productive to adopt the Japanese term, “kawaii”

While this term is often translated as, or at least closely associated with, the English word “cute” and its meaning (Cheok & Fernando, 2011), more correctly describing something as kawaii draws attention to a potential for playfulness, “an inquisitive attitude” and the ability to surprise people to catch them “off guard” (Cheok & Fernando, 2011)

The idea of Haru’s ability to surprise people resonates with the importance of “interruption” in phenomenological perspectives on encounters between selves and others where difference plays a key role (Pinchevski, 2005; Sandry, 2015)

As opposed to being non-threateningly familiar, Haru thus has the potential to be quirky and unusual, drawing people’s attention and inviting their participation in continued communication

[SLIDE 12]

Sociocultural perspective

Defining Haru as kawaii is complicated by the fact that different people, and even the same person across changing circumstances, may or may not choose to appraise the same object as kawaii (Nittono, 2016)

The shifting attribution of the term kawaii depending on the preference of individual people and changes in context raises the importance of considering a sociocultural perspective on communication in human interactions with Haru

This perspective analyses communication as a means of producing, reproducing, and negotiating shared understandings of the world (Carey, 1992; Craig, 1999), heavily reliant on the overarching cultural setting as well as the detailed context of an interaction between particular individuals

[SLIDE 13] [3] Continuing development and research with Haru

A consideration of sociopsychological, cybernetic-semiotic, phenomenological and sociocultural perspectives on interactions with Haru suggests that it is useful to adopt a more dynamic understanding of communication overall, which could be important across design and prototyping contexts, as well as in planning user studies

From a dynamic systems perspective, communication is not about the transmission or exchange of fixed pieces of information, because, as Alan Fogel argues, “information is created in the process of communication”, such that “meaning making is the outcome of a finite process of engagement” (2006, p. 14)

This shifts a cybernetic-semiotic focus from a preoccupation with clear and precise messages, to considering the value of iterative exchanges of feedback and response through which meaning emerges

It also reinforces the idea that sociopsychological persuasion may rely not so much on any fixed perception of “cuteness” or even “kawaii”, but rather on a personality that develops and changes within and between interactions, dependent on context and individuals involved

In particular, although Delstarte’s idea of coding emotions for performance is a practical part of the design process discussed in above, considering how emotional communication can emerge through dynamic interchanges highlights the potential for an alternative acting paradigm to play a part

This alternative view is typified by the Stanislavski technique, within which performers are expected to coordinate with one another in the moment of interaction, behaving in ways shaped as reactions or responses to other performers (Moore, 1960; Hoffman, 2007)

When human-robot interactions are considered from this perspective, the precise coding of emotion or of information becomes less important than the ability of the robot to respond to changes in its environment as well as to the particular person with which it is currently engaged in interaction

[SLIDE 14]

A focus on dynamic communication, draws attention to the potential for nonverbal, embodied communication to support exchanges that are not restricted by turn-taking, but rather become continuous processes “within which signs can overlap even as they are produced by the participants” (Sandry, 2015, p. 69)

Not seen in this interaction with Haru playing rock, paper scissors – heavily reliant on turn-taking – but to be a focus in the future

[SLIDE 15]

Alongside this, while development of Haru beta concentrated on designing the robot’s body to allow expressive emotional communication, this robot will also need to communicate flexibly in a range of other ways if it is to fulfil the goal of being a platform to support human-robot communication research more fully

The continuing development of Haru adopts a broad understanding of what constitutes communication as “a triple audiovisual reality” (Poyatos, 1997) using verbal language (speech itself), paralanguage (tone of voice, nonverbal voice modifiers, and sounds), and kinesics (eye, face, and body movements) from human communication, extended in Haru using nonhuman communication channels, such as harumoji (on smart devices) and the projection of content onto nearby surfaces

[SLIDE 16]

The full paper goes into the various contexts within which Haru is likely to be situated for research, from my perspective I have been thinking what work I can contribute, in particular towards the idea of investigating responses to Haru in the long term

Autoethnographic/autohermeneutic research

Then moving into user experience studies extending this

[SLIDE 17] Questions and contact information

Twitter: @elsand

Email: e.sandry@curtin.edu.au

References

Carey, J. (1992). Communication as culture: Essays on media and society. New York: Routledge.

Caudwell, C., & Lacey, C. (2019). What do home robots want? The ambivalent power of cuteness in robotic relationships. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 135485651983779. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856519837792Craig, R. T. (1999). Communication theory as a field. Communication Theory, 9(2), 119–161.

Cheok, A. D., & Fernando, O. N. N. (2012). Kawaii/Cute interactive media. Universal Access in the Information Society, 11(3), 295–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-011-0249-5

Craig, R. T. 1999. “Communication Theory as a Field.” Communication Theory 9(2):119–61.

Fogel, A. (2006). Dynamic systems research on interindividual communication: The transformation of meaning-making. The Journal of Developmental Processes, 1, 7–30.

Gomez, R., Galindo, K., Szapiro D., & Nakamura, K. (2018). “Haru”: Hardware design of an experimental tabletop robot assistant. Session We-2A: Designing Robot and Interactions, HRI’18, Chicago, Il, USA.

Hoffman, G. (2007). Ensemble: Fluency and embodiment for robots acting with humans (Ph.D.). Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Levinas, E. (1969). Totality and infinity. Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press.

Maltby, R. (2003). Hollywood cinema (2nd ed.). Malden MA: Blackwell Pub.

Moore, S. (1960). An actor’s training: The Stanislavski method. London: Victor Gollanz Ltd.

Nittono, H. 2016. The two-layer model of ‘kawaii’: a behavioural science framework for understanding kawaii and cuteness. East Asian Journal of Popular Culture 2(1), 79-95.

Pinchevski, A. (2005). By way of interruption: Levinas and the ethics of communication. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Dusquene University Press.

Poyatos, F. (1983). New perspectives in nonverbal communication studies in cultural anthropology, social psychology, linguistics, literature, and semiotics. Oxford; New York: Pergamon Press.

Poyatos, F. (1997). The reality of multichannel verbal-nonverbal communication in simultaneous and consecutive interpretation. In F. Poyatos (Ed.), Nonverbal communication and translation: New perspectives and challenges in literature, interpretation and the media (pp. 249–282). Amsterdam; Philadelphia: J. Benjamins.

Sandry, E. (2015). Robots and communication. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Simmons, R., Makatchev, M., Kirby, R., Lee, M. K., Fanaswala, I., Browning, B., … Sakr, M. (2011). Believable Robot Characters. AI Magazine, 32(4), 39. https://doi.org/10.1609/aimag.v32i4.2383

Stahl, C., Anastasiou, D., & Latour, T. (2018). Social Telepresence Robots: The role of gesture for collaboration over a distance. Proceedings of the 11th PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments Conference on – PETRA ’18, 409–414. https://doi.org/10.1145/3197768.3203180

Sutherland, C. J., Ahn, B. K., Brown, B., Lim, J., Johanson, D. L., Broadbent, E., … Ahn, H. S. (2019). The Doctor will See You Now: Could a Robot Be a medical Receptionist? 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 4310–4316. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICRA.2019.8794439

Turkle, S., Breazeal, C. L., Dasté, O., & Scassellati, B. (2004). Encounters with Kismet and Cog: Children respond to relational artifacts. IEEE-RAS/RSJ International Conference on Humanoid Robots. Presented at the Los Angeles. Los Angeles.

Zachiotis, G., Andrikopoulos, G., Gomez, R., Nakamura K., & Nikilakopoulos G. (2018). A survey on the application trends of home service robotics. Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biometrics, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

© 2025 Zigzaggery

Theme by Anders Noren — Up ↑