All this talk about perspectives, windows, maps and travelers etc. and no mention of robots… well, I’d better do something about that!

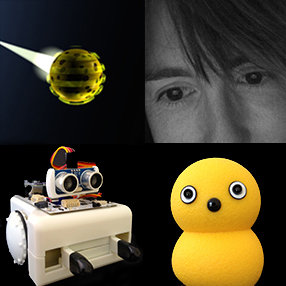

Alan, Brad, Clara and Daphne are “cybernetic machines” designed and built by the artist Jessica Field. They are all linked together to form an art installation, a system that is able to perceive human visitors. I saw these ‘robots’ when I was in Canada in 2007, at the Musée des beaux-arts de Montréal as part of the Communicating Vessels: New Technologies and Contemporary Art exhibition.

Semiotic Investigation into Cybernetic Behaviour from Jessica Field on Vimeo.

Alan, Brad, Clara and Daphne can’t move around, so they can’t really be thought of as travelers, but the ‘conversation’ between Alan and Clara offers an extreme illustration of interaction between beings that perceive the world from incommensurable perspectives. Alan is able to sense the motion of visitors over time, whereas Clara senses their distance from her in space. Alan and Clara’s perceptions of their environment are communicated to human visitors by the other two robots/computers in the system. Brad produces noises indicating particular aspects of their emotional state or “mood”, while Daphne translates their interactions into a conversational exchange in English. Although Alan and Clara aren’t really communicating with each other directly, their potential interaction is played out for visitors to the installation. As you move around the room you begin to ‘experiment’ with the robots (at least that’s what I did) in order to try to work out what their conversation means, what they can and cannot ‘see’.

Alan and Clara’s conversation highlights the difficulty involved in discussing the world with an other that senses its environment in an entirely different way from you. They see the world through different windows, and most of the time they are unable to agree on what is happening. Occasionally, Alan and Clara both ‘catch sight’ of a visitor at almost the same moment, “WOW! YOU SAW IT TOO”, and they are able to agree that something is there, but for much of the time the conversation is one of confusion over what, if anything, is out there in the installation space.

The difficulty in their interaction unfolds in part because of the extreme difference in their perceptions, but also because Alan and Clara are unable to develop any strong sense of trust for each other or respect for the other’s judgement. This means that, while they appear to find their disagreements over what is in the room unsettling, they don’t take any steps to try and work together in developing a sense of what is happening in the room. Of course, the installation is designed precisely not to explore this idea, but rather to focus on the incommensurable nature of Alan and Clara’s ideas about the world. It offers a great illustration to help explain why I’m particularly interested in how trust and respect can develop between disparate team members who sense the world in different ways. Attaining a level of trust and respect is key in effective human-dog teams for example, and I think it could also be vital in human-robot teams.