Emotional Robot Design

These are the notes for a talk, Emotional Robot Design and the Need for a Humanities Perspective, presented at The Future of Emotions conference, 14 June, 2018 at the University of Western Australia

[SLIDE 1] Emotional Robot Design and the Need for a Humanities Perspective

I have used a particular paper, Monique Scheer’s, “Are emotions a kind of practice”, and the Bourdieuian approach to understanding emotion as practice it employs, to shape aspects of this presentation, which I hope is helpful to people attending this conference, given Scheer’s focus on history of emotions research in her paper

[SLIDE 2] Outline

[1] Introduction to robots, bots and emotion

[2] Theorising emotion in robot and bot design

[3] Emotional practice in dynamic human-robot relations

[1] Introduction to robots, bots and emotion

From the first time the term robot was used in Karel Capek’s play Rossum’s Universal Robots robots, feelings and emotions have been juxtaposed

[SLIDE 3] Karel Çapek – R. U. R.

Rossum’s robots have no emotions or feelings in the beginning of the play

Later given the ability to sense pain, so avoid damage to their fragile, organic bodies

Towards end of play emotions begin to emerge in the robots, details of this process unclear, but it seems some are built with a “level of irritability” to make “them into people”

[SLIDE 4] Star Trek: The Next Generation – Data

Data is an android that cannot feel, and whose communication is precise and lacking in emotion

Data’s early lack of emotion is valued, placing him as the ultimate rational thinker and communicator, the captain wishes he and the crew “were all so well-balanced”

In fact, it is clear that Data has learnt the appropriate human emotional responses to different situations

But Data also wants to find a way to feel – and therefore to connect better with humans

To develop his humanness, through telling jokes, performing music, painting etc often somewhat unsuccessfully (lacking in timing/nuance)

This is only possible with when the emotion chip is located

[SLIDE 5] The “emotion chip” effect

Unfortunately, the first time this is put to use, it “overloads his neural net” such that he can no longer operate effectively

It is clear that Data must learn to control his newfound feelings, and thus the story illustrates the way emotions are often seen as “potentially or actually subversive of knowledge” an observation made by the feminist theorist Alison Jaggar

More recently Humans and Westworld have continued to question the relationship between robots and humans, emotions and feelings (in their own very different ways)

[SLIDE 6] Hanson Robotics – Jules and Sophia

In real life, we have robots such as these from Hanson Robotics

While Jules could be described as an emotional robot, with a moving expressive face, it is difficult to argue that this robot is doing more than pulling the appropriate faces in time to scripted speech.

The same could be said for Sophia, although this robot’s expressions are likely somewhat more realistic than for Jules

In spite of their shortcomings, Hanson wants such robots to “evolve into socially intelligent beings, capable of love and earning a place in the extended human family”

[SLIDE 7] Microsoft – Zo and Soul Machines – Ava

While robots like Jules and Sophia are seen by some as falling into the uncanny valley, where a robot is close to seeming to be human, but not quite, resulting in a sense of intense discomfort, even horror

It is easier for bots (software robots) to appear humanlike through their use of text or voice

Zo is a chatbot on a number of platforms, whereas Ava is designed as a helpdesk operator, with a highly expressive computer generated face

(Note: it is difficult to show the popular fictional version of this, but the best known is probably the voice of the operating system, Scarlet Johannsen, in the film HER)

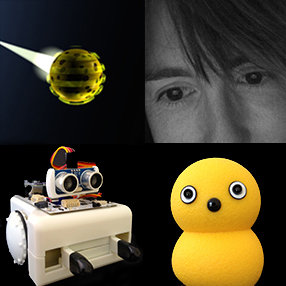

[SLIDE 8] Kismet and Jibo

Caricature designs such as Kismet and more recently Jibo, are a way for physically instantiated robot to avoid uncanny valley

The goals for these robots sound similar to those for Hanson’s

For Cynthia Breazeal, a social robot should be “socially intelligent in a humanlike way”

Her aim being to make people’s interactions with the robot like “interacting with another person”

For Kismet this was through an expressive face and babble (not fully formed speech)

Jibo has an expressive body and “eye”, and talks in fully formed language

Jibo treats “you like a human being”, with the aim of developing “meaningful relationships” and becoming “one of the family”

Broadly, Breazeal’s aim is to “humanize technology”

[SLIDE 9] Humans have “an emotional life”…

In 2005, Sherry Turkle noted that humans have “an emotional life” that differentiates them from computers.

As you can see, the situation may have got more complicated with social robot and socialbot developments

Fictional narratives often play with the idea and real-life creators see various reasons for making robots that at least seem emotional (in ways that support people’s sense that they might also feel without correction)

[2] Theorising emotion in robot and bot design

[SLIDE 10] Emotions, feelings and reason

Some roboticists (eg Brooks and Breazeal) have drawn on the work of Antonio Damasio to argue that emotions are important more generally, following Damasio’s argument that “emotions and feelings may not be intruders in the bastion of reason”; rather, “they may be enmeshed in its networks, for worse and for better”

For Monique Scheer, as for Damasio, emotions are ways to engage practically with the world

While Damasio works from his own research in neuroscience, Scheer draws on Pierre Bourdieu’s “habitus” to emphasise the “socially situated, adaptive, trained, plastic, and thus historical” body whose practices include “mobilizing, naming, communicating, and regulating emotion”

[SLIDE 11] Emotions, feelings and Data

While Scheer decides to use the terms emotions and feelings interchangeably, in research relating to robots it seems helpful to work with Damasio’s distinction between emotions as externally expressed, and thus visible to others; and feelings, as the “inwardly directed and private” thoughts “engendered by those emotions”, only available to others through a process of introspection and description

Data’s expression of emotion without the presence of underlying feelings illustrates this idea and it is also significant when considering the emotional expressions of robots and bots in real life

[SLIDE 12] Doing emotions and having feelings

Monique Scheer clarifies that, in general, emotions are not only something humans do, but also something they have

I might suggest that for robots, in general, emotions are also something they do, but feelings are something they don’t have (unless the emotion chip is developed in real life)

[SLIDE 13] Recognising and responding to emotions in others

The embedding of emotional understanding as well as expression is seen in some robots

Kismet for example, could read emotional cues in human conversational partners’ tones of voice and responds to them

Ava does this too, not just reading tones of voice, but also asking that people enable the computer’s camera so she can watch their faces and respond to their expressions with her own expressive and extremely humanlike face

As an example of a physically instantiated robot (as opposed to socialbot Ava), Kismet’s designers simplified the task of processing and producing expressions somewhat through use of the cartoonlike face and drawing on Paul Ekman’s idea of basic emotions – happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, surprise – as a way of coding emotions for the robot

Emotions are also coded in emoticons and emojis by many chatbots and bots such as Zo (again in comparison with Ava)

[SLIDE 14] Coding emotions – from humanlike to machinelike

Acting theory, in particular Delsarte’s system specifying the poses actors should use to communicate specific emotions to their audience, is another way to think about the coding of emotion

Kismet uses facial expressions to convey specific emotions, alongside head and neck movements, but more machinelike robots such as AUR, the robotic desk lamp, are also able to code bodily movements to express emotions (along the lines of the Pixar lamp), in this case because of lamp body’s relatively well-defined neck, head and face

However, AUR’s designer Guy Hoffman, was also interested in aspects of Stanislavski technique, in particular relating to the way actors must learn to be responsive to one another, coordinating their behaviour, and therefore how this might help human-robot interactions

In the case of AUR, Hoffman tested how this might work through an experiment where people complete a joint task with AUR, consisting of repeated moves that both human and robot learnt as they responded to each other’s movements

He monitored how the team’s performance improved, but also asked people how they felt about working with the robot, noticing how small unplanned motions, such as a double-take indicated the robot’s confusion when the person misdirected its next move

Interactions between AUR and humans were shaped not only by the experimental context, but also the way they were required to work closely together

People felt responsibility for this robot

[SLIDE 15] A “feel for the game”

Scheer notes that “Practice theory is more interested in implicit knowledge, in the largely unconscious sense of what correct behavior in a given situation would be, in the ‘feel for the game’”

This can be seen in the movements of AUR and a human working towards completion of a joint task, but maybe even more strongly in Shimon (Hoffman’s Marimba playing robot that performed improvisational jazz with human musicians) and in Sougwen Chung’s collaborative drawing with D. O. U. G._1 and 2

Shimon nods along with the music, and uses its head, neck and gaze, to look around and at the human musician, passing control for the improvisation through these cues

I’ll discuss Chung’s interactions with D. O. U. G. in a moment

In these interactions, humans may form an emotional bond with the robot, at least during the interaction, aiding a nuanced performance of music or a drawing

[SLIDE 16] Subjects and objects as a product of practices

To understand these dynamic interactions between humans and robots it is useful to consider how, for practice theory, “subjects (or agents) are not viewed as prior to practices, but rather as the product of them”

This has much in common with arguments from Donna Haraway and here Barbara Smuts, who suggests that human-other relations (she is most interested in human-animal relations) can best be thought of as “a perpetual improvisational dance, co-created and emergent, simultaneously reflecting who we are and bringing into being who we will become”

In drawing with D. O. U. G., Chung notes the ease with which she assigns agency, but also personality and intent to the robot D. O. U. G. has an expressive personality

[SLIDE 17] Bodies, histories and practices

As the quote on the previous slide from Smuts indicates, the relational dance does reflect “who” or “what” the participants are, as well as bringing them into being together

Scheer explains further, “The body thus cannot be timeless; it contains history at multiple levels” including “its own history of constantly being molded by the practices it executes”

While Drawing Operations Unit Generation One did draw in the moment with Chung, the second iteration of this robot learns from Chung’s past work, before human and robot work together to produce more sophisticated drawings as seen here

[3] Emotional practice in dynamic human-robot relations

[SLIDE 18] Emotional practice and practice theory as the basis for a methodology

Scheer argues that “Viewing emotion as a kind of practice means recognizing that it is always embodied” which means “that an emotion without a medium for experience cannot be described as one”

But where does this leave robots and bots – while it can be argued that both are embodied (for bots in a computer, device or network) they may express emotion in response to something they sense, but they effectively do not experience the emotion, they do not feel (at least not in the same way as humans)

Theorists such as Turkle in Alone Together, consider technologies including social robots and socialbots as imposters, precisely because they appear to express emotions but do not have feelings

However, attending more closely to interactions between humans and robots may offer another way to assess human-robot relations, in particular where non-humanlike robots are concerned

Scheer argues that adopting practice theory as the basis for a methodology “entails thinking harder about what people are doing” as well as “working out the specific situatedness of these doings”

For my research, it is also important to think about what technologies are doing alongside people in those same specific situations

Looking at what people and technologies are doing together leads me to think beyond the assumed importance of “basic emotions”, “human emotions and humanlike emotions” to look at what non-humanlike technology does and how this is interpreted, not making the assumption that to be humanlike is the best or only way, and then looking for the truth of this in experiment, but rather analysing what happens when people meet all sorts of robots and bots…

[SLIDE 19] From humanlike robots to robots with their own emotional practices

Broadly, I think humanities perspectives, such as Scheer’s, help uncover how complicated questions about emotions, feelings, technologies and human relations with them are

It’s not enough to say you don’t want people to build emotional robots (although you might not want them to build humanlike robots)

All machines that move and interact with people will be read as somewhat emotional

Importantly, emotion can be identified as a key part not just of friendly social interaction but also of value in situations where a robot needs a human to help or respond

In cases such as D. O. U. G., but also in relation to EOD robots and even robotic vacuum cleaners, I have argued elsewhere that the human emotional response to a robot is an important part of working with the robot

For example, if your robotic floor cleaner gets stuck under a piece of furniture or against a rug, I bet you’ll interpret it as making a whine of frustration, which might draw you to assist

If robots have their own emotional practices, as opposed to mimicking human practices as closely as possible, these can reinforce their otherness, these practices will be read/named/coded, ie they will be interpreted (often in relation to human experience, ie anthropomorphised), but still be recognised as clearly not the same as human practices

Scheer notes difficulty of naively empathising with emotions found in sources for historical research – because the researcher’s body is likely trained differently from the bodies of those being read – but this is always a problem I think, not just for historians and sources, but when in the presence of any other

Machine others may have an advantage in reminding people of their unsure attribution of emotion

This might all seem open to the critique that it is only about human attributions, interpretations and responses, that the robots themselves are not emotional agents

But within the human robot and human bot interactions just discussed, it is vital not to overlook the activity of the machine in eliciting human attributions of agency and emotion Drawing on Peter-Paul Verbeek, I’d argue that a bot or a robot is a technology “characterized not only by the fact that it depends on our interpretation of reality, but also by the fact that it intervenes in reality” (Verbeek, 1995, p. 66)

The effects of technology, and therefore the effects of the robots discussed here, cannot therefore “be reduced to interpretation” (Verbeek, 1995, p.66)

The question of whether and how machines can be emotional therefore requires detailed critical assessment and analysis, for which a humanities perspective, such as the conception of emotions as “a kind of practice”, is particularly relevant, in particular when considering humans and robots in the moment of encountering each other, or as they continue to interact in a particular situation

Bibliography (a best attempt to indicate sources for quotations, but also more general ideas/narratives)